Since the 2015 Rhodes Must Fall campaign, calls to “decolonise the curriculum” have been ubiquitous within education, not least in former colonial powers whose modern populations contain groups with ancestry in colonised lands. Accordingly, there has been an admirable push to promote wider awareness of global histories, cultures, economics, legal systems, scientific developments and thought systems – as well as to consider these in the context of unequal power relationships.

On the other hand, some positions associated with “decolonisation” seem too didactic. They embrace straw-man representations of existing knowledge as semantically and politically homogeneous, expressing nothing but a blanket endorsement of colonial ideologies. So much so that supporters of the decolonisation agenda sometimes espouse simple inversions of colonial assumptions about the superiority of Western knowledge or culture. They can also assert the transcendental importance of one particular approach to interpretation, implying that alternatives entail complicity with colonial domination.

Take the claim by Rowena Arshad in a 2021 THE Campus article, “Decolonising the curriculum – how do I get started?”, that existing understandings of the world “have been grounded in cultural world views that have either ignored or been antagonistic to knowledge systems that sit outside those of the colonisers”. This makes for impressive rhetoric but overlooks the entire history of Western thinkers who have engaged constructively with forms of thought, culture or social organisation from Asia, Africa and Latin America. This includes some of the artists and intellectuals who were fascinated by the area once categorised as the “orient” – not all of whom adhered to imperialist views of the region.

The very meanings of “colonisation” and “empire” are far from straightforward even for formally constituted “empires”, as made clear by a comparison of the Umayyad Caliphate, the Holy Roman Empire and the British Empire. Other political entities not formally constituted as empires may have a comparable presence, as has been argued in the case of the modern-day US or China.

The relationship is far from simple between histories of empire and slavery and other phenomena studied in established academic areas. Furthermore, to properly engage with this requires a level of contextual knowledge, as well as knowledge more directly related to the phenomena in question. This can create significant difficulties in teaching because students’ prior historical knowledge is often patchy.

I have over a long period taught core modules that consider music in its historical, social, ideological and cultural context, primarily from the mid-19th century in Europe and North America. The music includes everything from Russian nationalistic operas to African American spirituals as harmonised and promoted by white Americans, musical representations of – and borrowings from – Africa, abstract “formalist” compositions produced during the Cold War and the growth of competing genres of soul, funk and disco. The context includes 19th-century European nationalism, the “Scramble for Africa” and slavery in the US, as well as social developments accompanying Western industrialisation and factors leading to World Wars, genocide, gulags and the more literal decolonisation in the decades following 1945.

However, it quickly became clear to me that students’ knowledge of this context cannot be assumed. To compensate, I have resorted to providing overviews of historical events (inevitably reflecting my own priorities and interpretations) before introducing students to the various musics in question. This is followed by basic discussions of existing interpretations of particular relationships, to facilitate students’ ability to consider such questions critically themselves.

Similarly, in a module on romantic aesthetics in music, art and literature, I preface discussion of orientalism and exoticism with a short overview of the history of colonialism and slavery involving the West – including the Al-Andalus and Ottoman Empires, alongside those centred in Britain, France, Spain, Portugal and Russia and so on.

Overall, judging by the quality of students’ work, this approach appears to have been successful. But the need to invest significant portions of teaching time to providing context underlines that some basic areas of socio-historical knowledge are not provided by secondary education. If they were, more advanced and nuanced tertiary study would be possible.

In the UK, prime minister Rishi Sunak recently announced his intention to require everyone to study some form of mathematics to the age of 18. I believe that improving school-leavers’ broad knowledge of global history (beyond the narrow nationalistic approaches urged by some politicians) is just as important as improving their mathematical abilities. Allowing pupils to drop history at age 13, unlike in other European countries, is not the way to facilitate that.

Ultimately, the prime minister’s intervention may lead to wider consideration of whether the existing A-level structure involves premature specialisation. Reforms would, in turn, necessitate an overhaul of university curricula to accommodate students who may enter their studies with greater experience of breadth than depth. But we should see this as a net gain.

In the case of “decolonisation”, students need to come to it with a wider knowledge of global empires and other key aspects of history. Otherwise, they will simply be reiterating ideologically approved reinterpretations of the past and its effect on knowledge without the capacity to critically assess these for themselves.

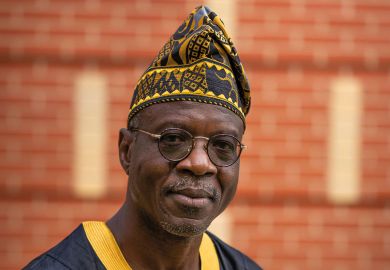

Ian Pace is professor of music and strategic adviser (arts) at City, University of London. He is writing in a personal capacity.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?