Universities should ramp up their contributions to the UK’s defence capabilities and prepare students for work in this field to help protect the country amid attacks on democracy, a vice-chancellor and security expert has said.

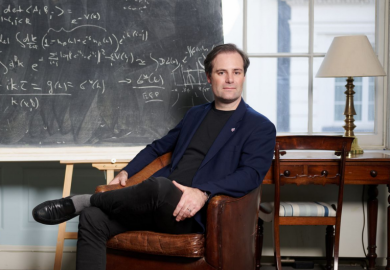

Anthony Finkelstein, president of City St George’s, University of London, says it is a “fundamental responsibility of the science and technology community, and of those of us involved in research and education, to contribute to defence”.

Writing in his blog, the former chief scientific adviser for national security to the British government addresses the ethical conundrums facing universities in recent years, as some students and staff continue to oppose institutions engaging with defence work and weapons manufacturing.

At some institutions, students have held protests over universities’ links to arms companies. Last year, King’s College, Cambridge said it would no longer invest in these organisations following student demonstrations.

Finkelstein writes: “I understand that there are colleagues who have moral reservations about defence, and in particular about the development of sophisticated military capabilities.

“I respect these reservations, but I do not share them, I believe they rest on a misunderstanding of the world ‘as it is’.”

He references renewed state-based aggression, particularly from Russia, whose behaviour is, he says, characterised by “conventional military power” as well as hybrid activity, including cyberattacks, espionage and disinformation.

He adds that conflict and fragility across the Middle East and parts of Africa “generate risks of terrorism, state collapse, migration pressures, and strategic shocks that reverberate beyond their regions of origin, directly affecting UK society”.

In the face of this, defence has become a key priority for the British government. Ministers have pledged to spend 5 per cent of the country’s gross domestic product on defence by 2035, while the sector appeared as a key “growth-driving” industry in Labour’s latest industrial strategy.

This means universities could also benefit financially from defence funding at a time when many are struggling to stay afloat.

But Finkelstein claims the “voice advocating for defence and security research is muted”, with universities rarely highlighting the defence work they do, despite most already engaging in some form of research in this area.

“It is, however, vital that UK universities grow and sustain their defence capability,” Finkelstein writes. “It is essential that they maintain deep engagement with our armed forces and with leading-edge defence companies, contributing both to UK prosperity and to the maintenance of sovereign technical capability. We must prepare our students for this work.”

Policy experts have previously suggested that universities need to find a “better way” of explaining why they partner with defence companies and the benefits of work of this nature in order to prevent a backlash.

Finkelstein says “accelerating technological change”, including advances in artificial intelligence, presents “significant research challenges to which universities are well placed to contribute”.

He also argues that defence research must engage with ethical and legal questions, as well as scientific ones.

“Universities cannot stand at a polite distance from defence and security,” he says.

“Defence research is not an awkward exception to academic purpose, but one of its most serious expressions. Universities should invest, partner, and lead in defence research with the same seriousness we bring to other national priorities.”

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?