When I took up my first academic post as assistant lecturer in sociology at the University of York in the late 1960s, I had no idea that there was any such occupational category as university administration.

I knew from my interview that Lord James of Rusholme was vice-chancellor and that my letter of appointment had been signed by someone called the registrar. But otherwise I assumed that the university was almost entirely managed by academics. It was, after all, academics who at that time staffed every major and minor committee even if they had no known competence in the area. (For years I chaired the Technical Staff Subcommittee, where I spent many happy afternoons arguing with philosophers and medieval historians about whether a glassblower in the physics laboratory had displayed sufficient competence to move on to a higher pay grade.)

My culpable ignorance of administrative work was eventually remedied by an invitation from the university’s newly appointed registrar, Anne Riddell, the first female chief administrative officer at a British university.

“Laurie. Would you be so kind as to come over to my office in Heslington Hall and answer an important question about the English department?”

I was happy to accept. Anne was a wonderfully insightful tactician who discharged all her duties with great efficiency while maintaining an endearingly patrician air which always suggested that she had rather better things to do with her time than manage a major university.

“Do you know Heslington Hall?”, she asked when I arrived. And she proceeded to introduce me to such esoteric administrative functions as estates and maintenance, finance, student liaison, admissions and planning before asking me “as a sociologist” to explain why so many academics in the English department at York spent quite so much time “hopping in and out of each other’s beds”. (I think I told her that their behaviour could only be the result of an overindulgent use of novels.)

At that time, back in the 1980s and 1990s, I was hardly alone among academics in believing that if administrators had any function at all then it was to offer a little background assistance to academics who, because of their higher vocational calling, became occasionally confused about such relatively minor matters as finance and admission and examination procedures. Their relative unimportance at the time is evident in the back page columns I wrote for what was then The Times Higher Education Supplement. There are plenty of lazy and incompetent dons (Dr Piercemüller loomed large) and a harassed departmental secretary (Maureen) but hardly a manager or administrator within parodic sight.

How different it all is now. Managers and administrators who once had a mute background presence are now a noisy part of the daily life of every scholar. Their ranks continue to swell even though the UK is already one of the very few countries in the world where non-academic staff already outnumber academics (see 'Staff profile: the age of the administrator', below). No wonder that my weekly Times Higher Education column is no longer stuffed with professors and readers but with directors of corporate affairs and human relations and the heads of research excellence framework strategy, overseas recruitment, research impact, fundraising, external relations and brand management. No wonder that what used to be a mildly patronising relationship between dons and their administrative servants has now become more and more like a battle for control.

When I was recently asked to address the annual conference of the Association of University Administrators on the manner in which this gap between managers and academics might be redressed, I refrained from the utopian suggestion that it could only truly be remedied if universities were no longer subject to their current marketing imperatives.

Instead, when I stood up to speak, I reminded my audience of the distinctive (and often unfortunate) presumptions that academics held about a university. I pointed out that no matter how effective each member of the audience might be at their respective task, their work would always be regarded by the typical academic as little more than pen-pushing. Compared with the rigours of intellectual life, running the finances of a university was, frankly, child’s play.

Neither could they as administrators ever hope for any degree of acceptance by academics as long as their roles might be characterised as management. The very word “manager” aroused academic hackles in much the same manner that the term “capitalist” stiffened the sinews of a Marxist.

But perhaps even more of a barrier to any reconciliation between the two tribes was the average academic’s resistance to any form of enthusiasm. Being discontented was somehow a guarantee of academic seriousness, an attitude that could not be vanquished by managerial injunction, a style of being only properly captured in the famous Jewish telegram: “Start worrying. Details to follow.”

And neither should administrators entertain any hope that academics might come to identify more and more closely with their university’s goals and mission statements. Academics persisted in regarding themselves as citizens of the world who had an inalienable right to criticise the institution that provided their temporary home. When under pressure to conform they could readily resort to universalistic concepts of “free speech” and “human rights”. And their ready access to the media ensured that they could always broaden what began as an institutional squabble into “a matter of principle”.

There were other incompatibilities. Academics felt that managerial demands for accounts of how they spent their time were philosophically flawed. How could one possibly place mundane time brackets around such a diffuse but essentially creative activity as “thinking”?

And then there was also the inequity of assessment. Whereas every academic was now increasingly subject to evaluation by means of such centralised devices as the REF, administrators seemed to go on their own sweet way, rewarding themselves without any clear evidence of how such rewards related to improved performance. And, of course, no one better exemplified this self-rewarding system than the fat vice-chancellor who sat at the head of his administrative army.

I left the last, and perhaps the most potent of what I chose to call “academic presumptions” until the end of my AUA address. Do you remember, I asked, the philosopher Gilbert Ryle’s story of the foreigner who wished to see a university? He was duly shown all the campus buildings but still complained that he hadn’t seen the university. Of course, Ryle’s point was that the university was not a thing but a set of elements. But that wouldn’t wash with most academics. They are the university. It is their names and academic titles that appear on the covers of books and the bylines of articles and the subtitles of the television screen and in the Nobel prize orations.

Is there anything, then, that administrators might do to remedy any of these impediments to cooperation? I suggested one answer to my audience. They might, I proposed, improve matters if they allowed academics to maintain their presumptions. And they might best do this by using a theatrical analogy. Actors are traditionally allowed to be sensitive, thoughtful, creative beings. They are also expected as part of their occupation to be temperamental and occasionally difficult. Their loyalty is not to any individual theatre but to “the theatre itself”.

Might not administrators improve their relationship if they presented themselves not as managers but as support staff to those upon the academic stage, as producers, property masters, scene setters, audience providers? What they must surely never do is to seek to occupy the stage themselves.

I’d like to be able to say that my address was well received. There was some modest applause but as I left the lectern I heard a noise that rather oddly for landlocked Nottingham resembled a receding tide. Only when I’d seated myself did I recognise it as the sound of collective seething.

Laurie Taylor is a sociologist, presenter of BBC Radio 4’s Thinking Allowed and author of Times Higher Education’s Poppletonian column.

Why did Laurie Taylor’s audience of university administrators seethe?

One reason is that the world is different now. I worked with Anne Riddell and Laurie – or Professor Taylor, as I still think of him – at the University of York in the early 1980s. In this golden age as a very junior and very generalist administrator, I was able to see the institution as a whole, to know academic staff in every department, and to know them as individuals to the point of recognising their handwriting and telephone manner.

In this golden age, too, respect was reciprocal. Early on in my time at York I supported a working group on admissions and public relations. After its report was published, one of the group’s members wrote to Anne praising my work in support of the group and the quality of the report I had written. Some 30 years on, Laurie has almost certainly forgotten that he wrote that letter. I haven’t.

Perhaps one of the reasons his audience seethed was because talk of a golden age can be painful for those condemned not to live in one. (Anyway it wasn’t entirely a golden age: but that is a topic for another article.)

So what changed?

The most striking difference is that virtually all universities are much larger than they were. The York of the early 1980s had about 3,500 students: the York of today has more than 15,000.

The range of administrative functions has also grown. Some of the new roles have emerged from within, often related to an institution’s financial survival. Others were created in response to external pressures such as teaching quality assurance, health and safety, and changes to the visa system. Still others have come in response to student expectations and requirements such as learning support and support for disabled students. Almost all these new roles are specialist. Few administrators would now claim to be a generalist.

Another reason the audience may have seethed is because the term “university administrator” is now too broad to be meaningful. The worlds of managers and administrators, of central administrators and administrators in academic departments are sharply differentiated. Administrators are no longer a job lot.

Somewhere along the line the relationship between academic and administrative staff worsened. My own view is that the developments in academic quality assurance in the 1990s were pivotal. For many academics, in the old universities especially, subject review inspections were an intrusion into their world; and the administrators that universities employed to mediate, translate and handle this new world were seen as intruders too. This is from an article written by Richard Roberts in The Tablet, October 1997: “A thought police now emerges from the academic woodwork to enforce academic management and ‘quality audit’. Here the Salieri principle applies: nothing gives greater pleasure to the guardians of competence than knowingly to suffocate real creativity. Salieri could not forgive Mozart his gift. He understood the nature of it, for he was himself a musician: but by the same token he understood how to destroy it.”

And if this language sounds lurid, I can recall a more recent disagreement with a well-known economics professor in which he told me that collaborative activity by university administrators in German universities in the 1920s and 1930s had caused the rise of the Nazi Party, and that my work in collaborating with the UK Border Agency over student visas was a direct parallel.

So another reason why the audience may have seethed is because many of the people in it will have experienced sophisticated professional and/or personal abuse of this kind. And if that is right, his proposed remedy may sound suspiciously like putting up with it.

So what advice would I give to the audience of university administrators on how to restore trust? I have three suggestions.

The first is to reflect on and sharpen the basic tools of your personal professionalism. Prose, for example, is now the medium in which academics and administrators interact, whether in emails or more formal papers; and writing well is a critical way to establish respect and trust. This is not about the right use of the apostrophe in “its”, although that is important. It is more about the voice you use in prose. Sometimes administrators adopt the vocabulary of managerialism; or the vacuousness of what my predecessor as academic registrar at the London School of Economics called “New Labour prose”; or the costive prose associated (often wrongly) with Civil Service mandarins, gnarled with polysyllables and passives. All these are signs of professional insecurity, and it is easy to avoid them. So question the words you use individually and lovingly. In particular, you must avoid the word “must”. And if prose is not your main medium, then reflect in the same way on numbers or presentation or, especially, the presentation of numbers.

The second suggestion is to be alert to the costs of what you are doing and to be able to explain and justify them. Benchmarking against peer institutions is one device, although it needs to be done sensitively. Also, the sector should surely be able to come up with a “performance indicator” showing the ratio of administrative to academic costs for each institution.

The third is to make a conscious point of seeing academics face-to-face. Visit them in their own offices, rather than expecting them to come to yours. This is about writing less and talking more, establishing personal relationships with individual academics, on their terms and in their environment.

Laurie’s talk touched a raw nerve in his audience. They know that a harmonious university, with good working relations between academic and administrative staff, is more likely to be an effective university. I have suggested some steps that individual administrators might take to this end. But unilateral action is only half a solution. This is in my view something that university managers and academics have to address, in the name of inclusivity and collegiality; and they have to address it urgently.

Simeon Underwood is academic registrar and director of academic services at the London School of Economics.

Staff profile: the age of the administrator

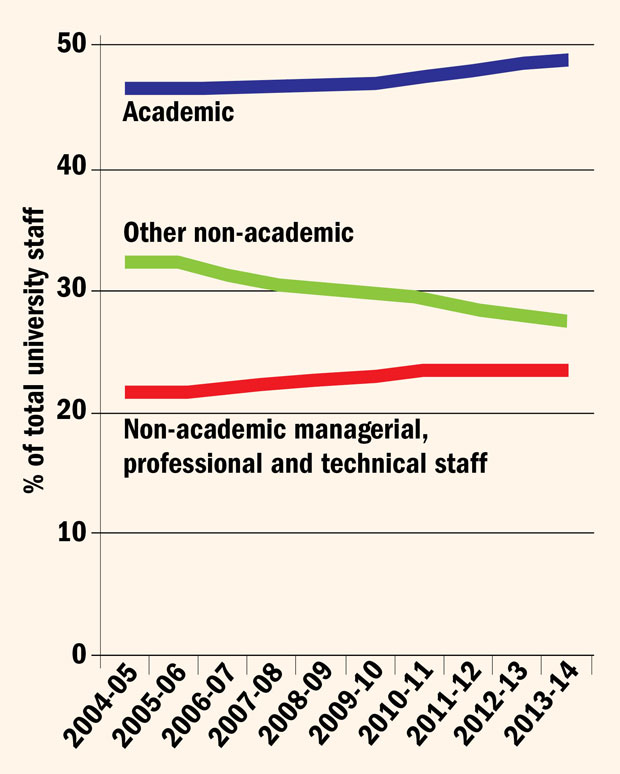

Non-academic staff at UK higher education institutions outnumber academic staff by 7,290 people, according to the latest data from the Higher Education Statistics Agency.

In 2013-14, the number of academic staff stood at 194,245 while the number of non-academic staff stood at 201,535.

In the past decade, the proportion of academic staff has grown – from 46 per cent of all staff in 2004-05 to 49 per cent in 2013-14.

But the fastest rate of growth in this period was in posts classified as “non-academic managerial, professional and technical staff”. The number of staff in this category grew by 25 per cent, climbing from 74,520 to 92,785, while the number of academic staff increased by 21 per cent.

The number of posts classed as “other non-academic” – a category made up of clerical and manual positions – declined by 2 per cent.

Times Higher Education reporters

POSTSCRIPT:

Article originally published as: Keeping the peace (28 May 2015)

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?