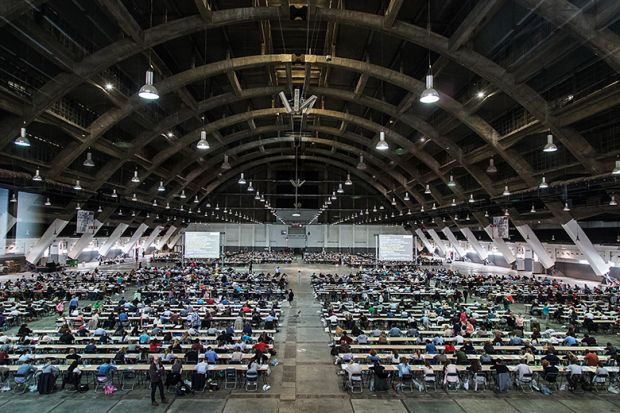

What is the defining image of the academic side of undergraduate life? For many centuries, it has surely been the student bent over the exam hall desk or library table, scribbling furiously. And although the modern library image would more accurately feature a computer screen with a vast amount of tabs open, the time spent sweating over exams or essays remains most graduates’ abiding memory of pursuing their degree. Assessment is at the heart of university life, and has a significant impact on what and how students learn – and, ultimately, what they go on to achieve.

And while there have been some innovations in assessment practice over the past decade, “there is still a huge reliance on closed book examinations and coursework essays in most subjects”, according to Neil Morris, director of digital learning at the University of Leeds.

There are many in higher education who have long believed that this “learn and regurgitate” assessment formula is not conducive to true learning. One recent paper that looks into alternative ways of examining students points to a wealth of research showing that memorisation is the “lowest level of learning”, as students quickly forget what they memorise. The paper, “Using principles of authentic assessment to redesign written examinations and tests”, published in January in Innovations in Education and Teaching International, notes that there is a strong knowledge-testing culture in many global regions, including South America, South-east Asia and the Middle East. However, “memorisation ill-equips students for the complex demands of life and work [because it makes it] difficult to engage in deep learning”.

According to Morris, the traditional focus of universities’ assessment practices on “knowledge recall, reasoning and structured writing” has the benefit of being scalable to large cohorts of students, allowing universities to ensure that each individual meets strict criteria for degree standards.

However, while this approach does cover some of the essential abilities needed in the workplace, it does not match employers’ increasing needs for a wider set of skills as the fourth industrial revolution begins to unfold, with the internet allowing instant access to vast swathes of knowledge and as artificial intelligence develops to the point where it can take on many traditional graduate roles. In Morris’ view, this means that the focus of modern universities should move away from knowledge retrieval and retention and on to knowledge assimilation, problem-solving and team-working.

Phil Race, a visiting professor of education at Edge Hill and Plymouth universities, agrees. For him, the cramming that traditional exams encourage is “far from how we access information in real life now, and will [remain anachronistic] until we have the internet in exams”. But, according to Jon Scott, pro vice-chancellor for student experience at the University of Leicester, it is important for universities to teach students to evaluate “how credible and reliable” various online knowledge sources are likely to be.

“Those skills are really important and it’s very important that those are tested,” he says. “The days where there was one textbook and you had to learn it are long gone.” And while all disciplines have a “fundamental knowledge base that students just have to know” – memory of which can legitimately be tested in an exam – the extent of that knowledge base varies by subject. Medical or law students, for instance, must be able to recall a fairly large amount of information without having to look it up if they are to be successful in the workplace. But other, less vocational subjects do not have the same imperative.

“The most important thing is making assessment much more akin to real life,” Scott says. “Some disciplines are closer to that already, while some have quite a long way to go.”

Over the years, many universities have adopted assessed essays as an alternative to exams, on the grounds that it allows for more considered reflection and removes the advantage offered by traditional exams to those who deal better with the pressure and can write faster. But Scott notes that, for the majority of subject areas, essays are not necessarily any more closely related to the way that knowledge is used in real life than exams are.

“For example, [in the workplace] you might need to write something very succinct. Writing something short is actually quite challenging and students should learn how to get their message across in that format,” he says. “Another area is how to handle data and how to present it, as the level of misuse of data by politicians and the press, for example, is frightening. You could do a timed activity under exam conditions, such as an interpretation of a piece of information or a piece of data, which requires students to demonstrate knowledge and use it effectively.”

With such an array of potential approaches, how is a university department to decide which to adopt? According to Emma Kennedy, education adviser (academic practice) at Queen Mary University of London, they need to ask: “What does success look like? What does your outcome at the end of the degree look like?” The answers to those questions "can be a bit lost in the way we assess current students”, she says.

“One thing that is really valuable that we don’t often do is rewarding students for taking notice of feedback and improvement,” she says. One way of doing that is known as ipsative assessment. It assesses students based on how well they have improved on their last assignment, rather than competing against their peers. It has yet to take off widely, but a 2011 paper by Gwyneth Hughes, a reader in higher education at the UCL Institute of Education, argues that adopting it would focus university assessment on genuine learning. According to the paper, “Towards a personal best: a case for introducing ipsative assessment in higher education”, published in Studies in Higher Education, “ipsative feedback has the potential to enable learners to have a self-investment in achievable goals, to become more intrinsically motivated through focusing on longer term development and to raise self-esteem and ultimately performance. An ipsative approach also might encourage teachers to provide useable and high quality generic formative feedback.”

For Jesse Stommel, executive director of the division of teaching and learning technologies at the University of Mary Washington, a public liberal arts and sciences university in Virginia, most assessment mechanisms in higher education don’t assess learning – despite universities’ claim that this is what they value most. “Meaningful learning resists being quantified via traditional assessment approaches like grades, academic essays, predetermined learning outcomes and standardised tests,” he says. Exams, meanwhile, are at their best when they are used as a formative tool for learning, he says.

“Our approaches treat students like they’re interchangeable…but not every student begins in the same place,” Stommel says. He believes that an approach called “authentic assessment” is more meaningful and enables students to take ownership of their learning, and to collaborate rather than compete with each other.

The idea of authentic assessment is at the crux of the debate about assessment in higher education, especially as the fourth industrial revolution transforms our ideas about what is needed from the modern graduate. It is focused on testing “higher-order skills”, such as problem-solving and critical thinking, through tasks that are more realistic or contextualised to the “real world”.

Opinion varies on what exactly constitutes authentic assessment, but almost all experts agree that appropriate exercises mimic professional practice, such as group activities or presentations.

Stommel says authentic assessment also gives students a wider audience for their academic work, such as their peers, their community and potentially even a digital audience. “For example, I’m a fan of collaborative assessment, which allows the students the opportunity to learn from and teach each other,” he says.

In some disciplines, authentic assessment is already in full effect. The “objective structured clinical examination” is a standard method used in medical schools. Students are observed undertaking particular practical procedures, such as taking a patient’s history or doing a blood test, allowing them to be evaluated on areas critical to healthcare professionals, such as communication skills and the ability to handle unpredictable patient behaviour.

Students also appear to appreciate authentic assessment. A 2016 paper by researchers at Deakin University, “Authentic assessment in business education: its effects on student satisfaction and promoting behaviour”, published in the journal Studies in Higher Education, looked at the use of authentic assessment in an undergraduate business studies course and found that it increased student satisfaction, especially among those who are highly career-oriented.

Redesigning assessment in this way has also been promoted as a method to reduce contract cheating. Although essays are able to test more than rote memorisation, they are particularly prone to this kind of cheating, and a 2018 survey estimated that as many as one in seven students had used the services of an essay mill.

To combat that problem, Louise Kaktiņš, a lecturer in the linguistics department at Macquarie University in Sydney, proposes the use of more in-class assessments, particularly exams.

“For all subjects…it should be compulsory to have both mid-semester exams and final exams,” Kaktiņš writes in a 2018 paper, “Contract cheating advertisements: what they tell us about international students’ attitudes to academic integrity”, published in Ethics and Education. “The only way to see the level of students’ output is to ensure that the majority of gradable work is incorporated into exams because an exam is the only thing that students cannot acquire via contract cheating,” she adds.

Thomas Lancaster, senior teaching fellow in Imperial College London’s department of computing, and Robert Clarke, a lecturer at Birmingham City University, have written extensively on contract cheating and have advocated the introduction of face-to-face examinations, or an oral component to complement written assessments.

Meanwhile, an Australian study, “Contract cheating and assessment design: exploring the relationship”, published in Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, found four assessment types that are perceived by students to be the least likely to be outsourced to essay mills: in-class tasks, personalised and unique assignments, vivas, and reflections on placements. However, according to the analysis of survey responses from 14,086 students and 1,147 educators in eight Australian universities, these are also the least likely forms to be set by educators. Only between a quarter and a third of lecturers said that they set such exercises with at least moderate frequency.

In 2016, the Australian government commissioned the same researchers to investigate the use of authentic assessment to tackle the problem. The resulting paper, “Does authentic assessment assure academic integrity?: Evidence from contract cheating data", forthcoming in Higher Education Research and Development, analysed 221 assignment orders to essay writing services and 198 assessment tasks in which contract cheating was detected. The results show that all kinds of assessment – authentic or not – were “routinely outsourced by students”.

“A lot of research and advisory documents from higher education quality bodies advise academics to use authentic assessment design as a way of ensuring academic integrity,” says Cath Ellis, associate dean (education) at UNSW Sydney. However, the research shows that “it doesn’t do what most people think it does. One thing you would assume was that if authentic assessment design did make it possible to design out contract cheating you wouldn’t see orders placed on contract cheating websites for these kinds of assessments. But, lo and behold, we found that assessment tasks were being contract cheated that were both authentic and not.”

Ellis points out that a lot of the academic articles making the claim that authentic assessment prevents cheating do not offer any evidence to substantiate it. “We hypothesise that people think that it will be effective because it makes assessment tasks so compelling or enjoyable that students won’t want to cheat,” she says.

The study's results do not entail that designing assessment effectively won’t reduce the use of essay mills or that academics shouldn’t set authentic assessment tasks, Ellis stresses. But universities should not become complacent and “stop looking for [cheating] or talking to students about it”.

Moreover, educators must not focus all their attention on designing assessment to stamp out contract cheating because that would be to the detriment of education and those who do not cheat, Ellis adds. In addition, authentic assessment is more time consuming for those who implement it, Ellis admits, and it can be hard to convince those working within the higher education sector to change, particularly at large, ancient institutions.

For Race, a better idea would be to switch to assessment via computer-based activities (with full access to the internet). This, he says, would have advantages over both exam- and essay-based approaches in that it would neither disadvantage slow handwriting nor offer any opportunity for cheating: “We know whose work it actually is if the technology can verify who’s using it and when,” he says.

But Kennedy of Queen Mary points out that there are external factors that can make changing the way universities do things difficult. For example, there are rules in the UK about being clear to students about what assessment they will experience and making sure that students on comparable degrees are assessed comparably.

Universities are expected by governments to rank students on their ability upon graduation, and employers want to know what particular degree classifications actually mean. Students, too, want to know what the value of their degree is, especially now that they are paying high fees, Kennedy says. “We don’t want to see them as consumers and they don’t necessarily see themselves as customers – which is commendable – but they are paying a lot of money and they do see it as an investment.”

All of this makes it difficult for universities to unilaterally transform their assessment practices.

Part of the concern around the meaning of degree classifications relates to the grade inflation that is perceived to have become rife in higher education in recent decades. The concern has been particularly high in the UK, with some suggesting that so many students now get a 2:1 or first-class degree that it would be better to move to a more granular way of grading them, such as a US-style grade point average, which gives an average mark based on assessments throughout the undergraduate years.

Observation of rising GPAs in the US has diminished initial hopes that such a switch could help address grade inflation, but advocates point to other benefits. A major one is that a GPA system lessens the stakes at exam time; although UK universities do implement assessments throughout the undergraduate years, a much higher weighting is accorded to end-of-year exams.

According to Kennedy, education scholars in the UK have recently become interested in the idea of a whole-programme approach to assessment. “Most [university departments] think about how they assess at a modular level, but students don’t take modules [in isolation]. It’s worth thinking about how different kinds of assessments are balanced across the programme,” she says. “Practically, you want to assess everything at the end, but that can put a lot of stress on students.”

That is particularly true for disabled students. Under a recent Twitter hashtag, “why disabled students drop out”, one student wrote that she found her degree's 10 days of three-hour final exams – which were the “be-all and end-all” of her course – too much to handle. “Assessments (almost) entirely exam based and pushed together at the end are inherently able-ist,” she wrote.

Mary Washington’s Stommel agrees. “Our approaches need to be less algorithmic and more human, more subjective, more compassionate,” he says. “Most of our so-called objective assessment mechanisms fail at being objective and prove instead to reinforce bias against marginalised populations.”

Moreover, Leicester’s Scott adds that “students need to know how they're getting on. If you don't have any assessment till the end, it’s very hard for them to tell.” For this reason, carrying out formative assessment throughout the learning process is very valuable – both for students and staff, allowing tutors to identify those who might need additional support. The problem, Scott warns, that it is often challenging to get students to engage with formative assessments if they don’t count towards the end degree result.

Race thinks that the solution is for universities to adopt a broad array of more learner-centred approaches to assessment, with “the mystery removed” such that students are able to “practise self-assessing and peer-assessing to deepen their learning of subject matter”. He also thinks teaching staff should be required to undertake continuing professional development to keep up with advances in assessment and feedback. This should both increase the quality and streamline the amount of assessment, he says.

But it is clear that such a world remains a long way off. As things stand, Race regularly meets “many lecturers for whom the burden of marking students’ work and giving them feedback has spiralled out of control”.

It seems that everyone – staff, students and employers alike – would benefit from a fresh approach.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Time to get real

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?