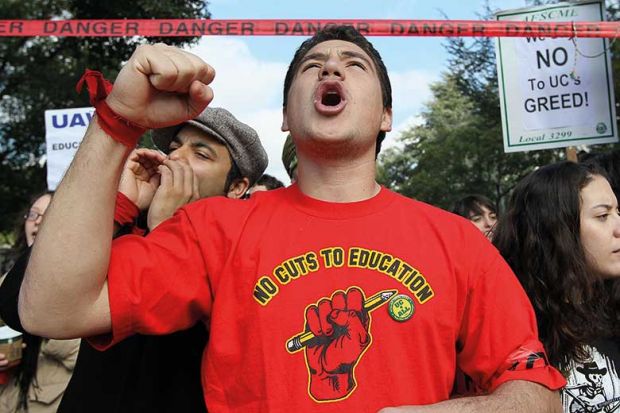

Critiques of the so-called neoliberal approach to higher education are nothing new. In essence, the charge is that supine university leaders, seduced by “managerialism”, have given up on making the case for a publicly funded education system.

Instead, they have prostrated themselves at the altar of privatisation and, into the bargain, have screwed over students and staff alike. To cap it all, they don’t give a fig for the underpinning values of the academy and are content to see research undermined and teaching debased.

A caricature surely? Well, not if Christopher Newfield’s The Great Mistake is anything to go by. And just in case you missed the point, an archetypally American subtitle, How We Wrecked Public Universities and How We Can Fix Them, rams the point home.

While Newfield denies that a grand conspiracy has been in place, he does identify a “long sequence of anti-egalitarian policy choices”. These are spelled out through an eight-stage “decline cycle” that forms the bulk of his book.

The different stages range from subsidies to private sponsors, through hikes in tuition fees, to cuts in funding impacting particularly badly on certain minority and disadvantaged groups.

Frustratingly, the overblown rhetoric obscures some interesting arguments. For example, Newfield shows how a growing consensus between Republicans and Democrats over the past 20 years, particularly in his home state of California, has made public universities vulnerable to funding cuts.

He is also right to identify the considerable pressure that students now feel from rising living costs, something that will be familiar to readers in the UK.

Newfield’s uncomfortable reflections on the cross-subsidy of research from teaching and the at times insatiable desire on the part of university presidents to enhance the prestige of their institutions also repay further attention.

Equally stimulating is his description of the capabilities that universities should seek to develop in their students. His straightforward and compelling list will be of interest to everyone who wants to promote research-led teaching.

But despite a final section that argues the contrary, there is no real attempt in the book to wrestle with the real and difficult choices that face policymakers and university leaders. To take just one example, there is the choice of whether or not tuition fees should continue to be funded largely or entirely from the public purse.

Fiscally, this approach has been shown to be unsustainable. It is also inherently unfair: students were benefiting from public subsidy at the same time as they were deriving substantial personal benefit from higher education. So asking them to contribute to the cost of their tuition seems more socially just than the – frankly elitist – alternative.

The charge of “privatisation” that Newfield makes is equally naive, unless the alternative is a command-and-control economy. In reality, most vice-chancellors make pragmatic choices on who does what, unencumbered by ideological baggage.

There are tired old comments throughout The Great Mistake about a boom in the number of administrators and the growth of expensive “Vegas-style” facilities. But clever slogans do not address the fact that universities are complex institutions that have to renew buildings and infrastructure to keep pace with demands from students and staff alike. Newfield also argues that US universities have retreated from promoting the public good, which feels like a gross generalisation. Indeed, it could be argued that despite competition from both established and new providers, public universities remain beacons of an inclusive and outward-looking society.

Although he focuses largely on the US higher education sector, the author makes common cause with critics of recent developments in the UK. But even the most strident voices in the UK academy would have to acknowledge that many of the problems described in this book simply do not apply here.

So whether it is untrammelled rises in tuition fees, the excessive influence of philanthropy, the emergence of new-style private universities or the vagaries of state funding, the US is not the UK. Our system may not be perfect, but UK universities have not been wrecked.

A final thought. Newfield describes his work as part of a newish tradition of “critical university studies”. In a way not untypical of the genre, he ascribes highly honourable motives to himself and his fellow scholars.

Those who take a different view – presumably anyone holding a leadership position in an American or British university – are made to feel venal, cowardly or stupid, and probably all three at once. While it may not be his intention, that is how Newfield’s arguments come across.

Whisper it, but university leaders do the job because they care about their institutions and the value, and values, of higher education more generally.

They may not always get it right, but presidents and vice-chancellors want to make our universities dynamic and intellectually challenging centres of thought, central to the health of democracy everywhere. The great mistake is to think otherwise.

Sir David Bell is vice-chancellor, University of Reading.

The Great Mistake: How We Wrecked Public Universities and How We Can Fix Them

By Christopher Newfield

Johns Hopkins University Press, 448pp, £24.50

ISBN 9781421421629

Published 14 January 2017

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Leaders share the sense of mission

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?